This article is about the ugliest, but potentially most useful piece of open-source software I’ve written this year. It’s messy, because UTF-8 is messy. The world’s most widely used text encoding standard was introduced in 1989. It now covers more than 1 million characters across the majority of used writing systems, so it’s not exactly trivial to work with.

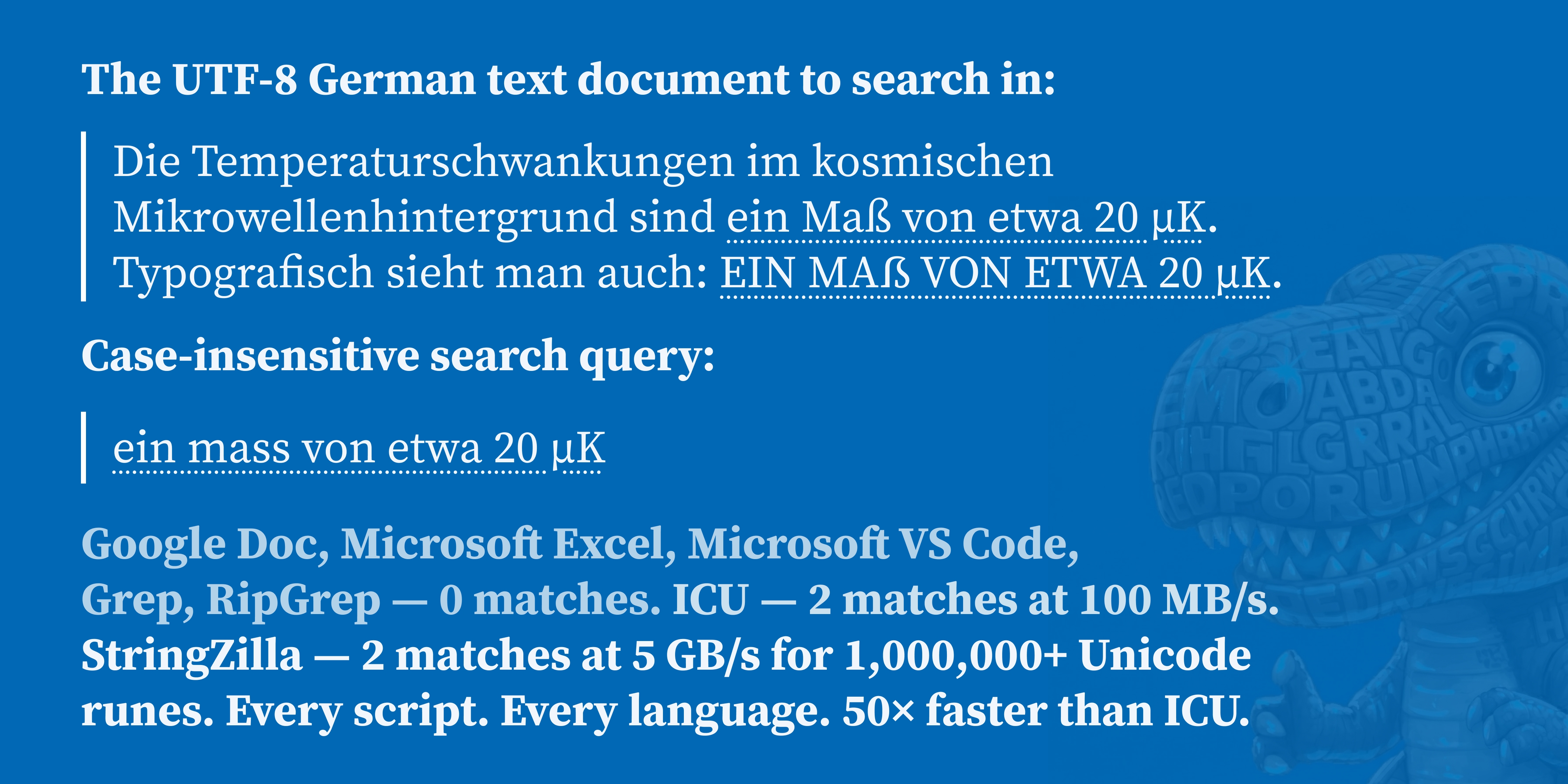

The example above contains multiple confusable characters: German Eszett variants 'ß'

U+00DF0x C3 9Fand 'ẞ'U+1E9E0x E1 BA 9E, the Kelvin sign 'K'U+212A0x E2 84 AAand ASCII 'k'U+006B0x 6B, and Greek mu 'μ'U+03BC0x CE BCvs the micro sign 'µ'U+00B50x C2 B5. Try guessing which is which and how they are encoded in UTF-8!

That’s why ICU exists - pretty much the only comprehensive open-source library for Unicode and UTF-8 handling, powering Chrome/Chromium and probably every OS out there. It’s feature-rich, battle-tested, and freaking slow. Now StringZilla makes some of the most common operations much faster, leveraging AVX-512 on Intel and AMD CPUs!

Namely:

- Tokenizing text into lines or whitespace-separated tokens, handling 25 different whitespace characters and 9 newline variants; available since v4.3; 10× faster than alternatives.

- Case-folding text into lowercase form, handling all 1400+ rules and edge cases of Unicode 17 locale-agnostic expansions, available since v4.4; 10× faster than alternatives.

- Case-insensitive substring search bypassing case-folding for both European and Asian languages, available since v4.5; 20–150× faster than alternatives. Or 20,000× faster, if we compare to PCRE2 RegEx engine with case-insensitive flag!

I’d like to stress that this is not just about “throughput” or “speed” - it’s about “correctness” as well! Some experimental projects try applying vectorization to broader text processing tasks, but the vast majority are limited to ASCII or ignore all the edge cases of Unicode to achieve speedups. StringZilla, however, is tested against a synthetic suite generated on the fly from the most recent Unicode specs, so when the 18.0 of the standard comes out, updating the library to support it should be trivial. It’s also tested against ICU on real-world data to keep it correct in typical cases. Let’s dive into the details of how this was achieved.

UTF-8 Primers

Today, almost all of the Internet is UTF-8. Its share grew from 50% in 2010 to 98% in 2024. The remaining ~2% is mostly legacy content in:

- “ISO-8859-1” or “Latin-1” — older Western European sites

- “Windows-1252” — legacy Windows encoding

- “GB2312” and “GBK” — older Chinese sites

- “Shift_JIS” — older Japanese sites

So what does it look like and how it improves on previous encodings?

If you often face those weird alternative encodings, just pull Daniel Lemire’s and Wojciech Muła’s simdutf.

Unicode Runes vs UTF-8 Encoding

Most trained developers know that UTF-8 is a variable-length encoding for Unicode codepoints.

It means that different characters may take different numbers of bytes to represent.

The first 128 codepoints (U+0000–U+007F) are represented as single bytes, identical to ASCII.

Codepoints from U+0080–U+07FF take 2 bytes, from U+0800–U+FFFF take 3 bytes, and from U+10000–U+10FFFF take 4 bytes.

Borrowing a table from Wikipedia, here’s how the encoding works:

| Codepoint Range | Byte 1 | Byte 2 | Byte 3 | Byte 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

U+0000–U+007F | 0xxxxxxx | |||

U+0080–U+07FF | 110xxxxx | 10xxxxxx | ||

U+0800–U+FFFF | 1110xxxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx | |

U+10000–U+10FFFF | 11110xxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx |

You typically parse it left-to-right, unpacking codepoints as you go.

With 32-bit integers you can safely represent any Unicode codepoint, but as you may notice, not all 32-bit integers are valid codepoints.

Even in the U+10000–U+10FFFF range, only ~2.1 million codepoints are valid, while the rest are reserved.

In a C99 implementation, a verification-free toy parser may look like this:

| |

As one may notice, there is some extra effort to compact the bits from multiple bytes into a single codepoint. It’s a modest amount of logic for modern CPUs, but the sequential dependency of processing $i+1$ byte after $i$ byte makes vectorization hard for modern CPUs. But not impossible!

Unicode in Modern Programming Languages

I’d argue, most developers don’t regularly need to parse Unicode codepoints from UTF-8 strings by hand.

A string is the first-class citizen of practically every modern programming language.

In Rust, for example, the char type represents a Unicode scalar value, and the standard library provides methods for iterating over characters in a string, like so:

In other languages, the situation is more complex, as some have previously standardized smaller representations for “characters”. A common thread at some point was to use fixed-width 16-bit “characters”, which can represent the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP) of Unicode, but not the entire range of codepoints. And when the need for full Unicode support arose, those languages had to introduce “surrogate pairs” to represent codepoints outside the BMP.

UTF-8 encoding also has a similar concept to surrogate pairs - “overlong encodings”. For example, the ASCII character 'A'

U+00410x 41can be represented in UTF-8 as a single byte0x 41, but it can also be represented using two bytes0x C1 81, three bytes0x E0 81 81, or four bytes0x F0 81 81 81. Those overlong encodings are invalid according to the UTF-8 standard and should be rejected by any compliant UTF-8 parser.

Moreover, UTF-8 has Emoji sequences that combine multiple codepoints into a single visual character via "ZWJ"

U+200D0x E2 80 8Dzero-width joiner. For example, the family emoji 👨👩👧👦 is a combination of 4 emojis: '👨'U+1F4680x F0 9F 91 A8, '👩'U+1F4690x F0 9F 91 A9, '👧'U+1F4670x F0 9F 91 A7, and '👦'U+1F4660x F0 9F 91 A6. Similarly, in Bengali script, the character "ক্ষ"U+0995 U+09CD U+09B70x E0 A6 95 E0 A7 8D E0 A6 B7(kṣa) is a combination of two consonants 'ক'U+09950x E0 A6 95(ka) and 'ষ'U+09B70x E0 A6 B7(ṣa) joined by a "Virama"U+09CD0x E0 A7 8D, which suppresses the inherent vowel sound of the first consonant.

That’s how we ended up with a mess like this:

- Rust:

Stringis guaranteed valid UTF-8. Indexed by byte, not char. - Go:

stringis UTF-8 bytes.runetype for code points. - Swift: Native UTF-8 (since Swift 5). Exposes grapheme clusters.

- Java: UTF-16. Compressed to Latin-1 (1 byte/char) since Java 9.

- C#/.NET: UTF-16. Always 2 bytes minimum (surrogate pairs for non-BMP).

- JavaScript: UTF-16.

"😀".length === 2(surrogate pair). - Python 3: Latin-1 / UCS-2 / UCS-4. Smallest fitting encoding.

- C/C++:

char*is bytes.wchar_tis platform-dependent.

For Python, in practice, it means that strings will massively explode in size when you add non-Latin-1 characters to them.

So if you are working on some web agents scraping HTML pages and wondering how to reduce memory consumption of your beautifulsoup4 objects, consider switching to UTF-8 encoded bytes instead of str.

If you only need to validate UTF-8 or convert it to UTF-16/32, Daniel Lemire’s SimdUTF is the way to go.

But if you need to search and manipulate it - read on:

Python not only knows how to deal with Unicode codepoints natively, but it also has a built-in unicodedata module that provides access to the Unicode Character Database (UCD).

It provides a subset of the ICU functionality, and where more is needed - there’s a PyICU Python binding one can pull from PyPi.

| Feature | Standard | PyICU | StringZilla |

|---|---|---|---|

| Character names and categories | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Canonical and compatibility decompositions | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Locale-agnostic case mapping | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Word, sentence, and line breaking | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Case-insensitive search | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Locale-aware case mapping and collation (sorting) | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Date, time, and number formatting | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Transliteration | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

StringZilla is less feature-rich than both. At least today. But it’s a lot faster for the most common operations. This time we’ll focus on just one of them - case-insensitive substring search.

Ideation & Challenges in Substring Search

Folding Expansions

Case-folding is the process of converting text to a form that allows for case-insensitive comparisons. It’s more complex than just converting uppercase letters to lowercase, especially in Unicode, where some characters have multiple case variants or expand into multiple characters when case-folded. For example:

- German: 'ß'

U+00DF0x C3 9Fand 'ẞ'U+1E9E0x E1 BA 9Eboth case-fold into "ss"U+0073 U+00730x 73 73. - Turkish: 'İ'

U+01300x C4 B0case-folds into "i̇"U+0069 U+03070x 69 CC 87- that’s a lowercase 'i'U+00690x 69plus a combining dot. - Ligatures: 'ffi'

U+FB030x EF AC 83case-folds into "ffi"U+0066 U+0066 U+00690x 66 66 69, so the original glyph contains matches for 'f'U+00660x 66, "ff"U+0066 U+00660x 66 66, "fi"U+0066 U+00690x 66 69, and "ffi"U+0066 U+0066 U+00690x 66 66 69queries.

Folding Invariants

Unicode 17.0 defines more than 1000 locale-agnostic mappings in CaseFolding.txt, with expansions up to 3 codepoints.

The obvious approach to case-insensitive search is to case-fold everything and then run memmem.

It’s also the slowest possible approach, and it breaks match offsets unless you keep an extra mapping layer.

StringZilla takes a different route: it tries very hard to find a fold-safe window in the needle - a slice that:

- Can be case-folded into ≤16 bytes.

- Doesn’t trigger surprises for a chosen SIMD path: no shrinking expansions, no ligatures, no folding targets like Kelvin sign.

- Has enough byte diversity to be a good SIMD filter.

To do that, we split Unicode into a handful of script-ish buckets and give each its own SIMD kernel and its own alarm rules:

- ASCII invariants (

00–7F): the cheapest kernel; most English letters, digits, and punctuation. - Western European (mostly 2-byte UTF-8): Latin-1 Supplement + Latin Extended-A, covering German/French/Spanish/Portuguese.

- Central European (mostly 2-byte UTF-8): Latin Extended-B and friends, covering Polish/Czech/Hungarian/Romanian.

- Cyrillic (

D0/D1lead bytes): Russian/Ukrainian/Bulgarian and other Slavic languages. - Greek (

CE/CFlead bytes): Greek and Coptic. - Armenian (

D4lead byte): Armenian. - Vietnamese (many 3-byte sequences): Latin extensions with diacritics and tone marks.

Most of those kernels are designed around 1- and 2-byte UTF-8 sequences, which already cover the majority of European languages. Vietnamese is the odd one out: it pulls in a lot of 3-byte Latin extensions with diacritics.

All of them not only differ in the folding kernels used on the hot path, but also in their alarm logic that triggers a slow-path verifier. Those alarms exist for two reasons:

- Some characters fold into targets you really don’t want to “just allow” in an ASCII fast path.

Example: 'K'

U+212A0x E2 84 AAfolds into 'k'U+006B0x 6B. - Some folds shrink or expand in ways that break “same length, same offsets” assumptions.

Example: 'ſ'

U+017F0x C5 BFfolds into 's'U+00730x 73.

This is why some ASCII letters are “unsafe” depending on where they appear. Not because they are rare, but because Unicode expansions can generate them. Here are a few that matter in practice:

- “k” is a folding target (Kelvin sign), so you can’t just treat it as a boring ASCII byte.

- “s” is a folding target (long s), and 'ß'

U+00DF0x C3 9Ffolds into "ss"U+0073 U+00730x 73 73. - “f” and “i” participate in ligatures like 'fi'

U+FB010x EF AC 81→ "fi"U+0066 U+00690x 66 69.

If you’d like to stare at the full ban logic, grep for sz_utf8_case_rune_safety_profile_ in the source.

It’s not poetry, but it’s deterministic.

Safe Window Selection

Most needles aren’t fully “safe”. So instead of folding the entire needle (slow, offset-hostile), we extract a window that is safe to SIMD-scan and use it as a pivot. The needle splits into three pieces:

needle (bytes): [ head ][ safe window ][ tail ]

needle (folded): [ .... ][ <=16 bytes ][ .... ]

SIMD scans only: [ <=16 bytes ]

Then every SIMD hit goes through a verifier that checks the head and tail around it.

The “why” is easiest to see on a tiny example.

The needle "faßade" contains 'ß'U+00DF0x C3 9F

, which is toxic for an ASCII fast path, but it also contains "ade":

needle chars: f a ß a d e

needle bytes: 66 61 C3 9F 61 64 65

folded bytes: 66 61 73 73 61 64 65 (ß → ss)

safe window: 61 64 65 ("ade")

So we SIMD-search "ade" and only then do the extra legwork for the "faß" prefix (and possibly tail).

To pick optimal safe windows, we follow this algorithm:

- Walk possible start positions in the needle, stepping by UTF-8 characters - never mid-character.

- For each start, fold forward and build per-script windows until you hit 16 bytes or an alarm.

- Score candidates by byte diversity to minimize false positives on the hot SIMD path.

- Pick the cheapest kernel that is both safe and applicable.

If the same window is safe for multiple kernels (e.g., pure ASCII), we pick the cheapest one so we don’t pay the Vietnamese folding tax for "xyz".

Why We Probe Last Bytes

This ties back to the UTF-8 primer: the continuation bytes (10xxxxxx) carry 6 payload bits each, while the leading bytes mostly encode the range.

In many scripts, that means the first byte is boring and the last byte carries the entropy.

Take Cyrillic as an example:

А Б В ... (Cyrillic alphabet)

D0 90, D0 91, D0 92 ... (leading byte repeats)

^^ ^^ ^^ (last byte differentiates)

If you probe the last bytes of UTF-8 characters, you get a much better SIMD filter: fewer false positives, less verifier work. So for windows with ≥4 UTF-8 characters we aim probes at the last byte of the 2nd and 3rd characters, plus the first and last bytes of the whole window. For very short windows probes overlap - that’s expected.

Serial Fallbacks: Danger Zones, Rings, and Hashes

Not every platform supports SIMD, let alone AVX-512. Some needles are too short, some scripts are too annoying, and sometimes an alarm goes off in the middle of a hot loop. StringZilla uses a few serial fallbacks that are still Unicode-correct:

- For needles that fold into 1/2/3 runes, we use a hash-free scan over the folded rune stream.

- For longer needles, we use a Rabin-Karp style rolling hash over folded runes with a small ring buffer, and verify on collisions.

- For “danger zones” detected by SIMD alarms, we scan for a cheap 1-rune candidate and validate the full match with the same head/tail verifier.

That’s pretty much the core idea of StringZilla v4.5. Let’s look at the numbers.

Performance Benchmarks

The following numbers are obtained on the Leipzig Wikipedia corpora, providing 100 MB+ of real-world text data for each language. The machine used was an AWS instance with AMD Zen 5 CPUs. For context, only a subset of those scripts are cased (have upper/lowercase distinctions):

- Latin basic range covers 🇬🇧 English, 🇮🇹 Italian, 🇳🇱 Dutch.

- Latin extended range covers 🇩🇪 German, 🇫🇷 French, 🇪🇸 Spanish, 🇵🇹 Portuguese, 🇵🇱 Polish, 🇨🇿 Czech, 🇹🇷 Turkish, 🇻🇳 Vietnamese with various Accents, Háčky, and Tones.

- Cyrillic covers 🇷🇺 Russian, 🇺🇦 Ukrainian.

- Distinct alphabets cover 🇬🇷 Greek and 🇦🇲 Armenian.

Other languages/scripts like 🇮🇱 Hebrew, 🇸🇦 Arabic, 🇮🇷 Persian, 🇧🇩 Bengali, 🇮🇳 Tamil, 🇯🇵 Japanese, 🇰🇷 Korean, and 🇨🇳 Chinese are caseless, and are included to demonstrate StringZilla’s ability to scan through arbitrary text without losing performance.

AVX-512 Against Serial StringZilla

Before comparing to other libraries, StringZilla first implements serial baselines for all APIs it provides for CPU architectures that don’t support some of our favorite fancy SIMD instructions.

| Dataset Language | Base, GB/s | SIMD, GB/s | SIMD Gains | Dataset Language | Base, GB/s | SIMD, GB/s | SIMD Gains | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🇬🇧 Eng | 1.15 | 10.93 | 11.9× | 🇮🇹 Ita | 0.81 | 10.63 | 14.7× | |

| 🇳🇱 Dut | 0.85 | 10.91 | 13.3× | 🇩🇪 Ger | 0.74 | 9.36 | 13.6× | |

| 🇫🇷 Fra | 0.73 | 8.37 | 15.1× | 🇪🇸 Spa | 0.99 | 8.86 | 10.8× | |

| 🇵🇹 Por | 0.77 | 9.58 | 14.3× | 🇵🇱 Pol | 0.62 | 7.51 | 14.2× | |

| 🇨🇿 Cze | 0.43 | 6.10 | 17.1× | 🇻🇳 Vie | 0.41 | 6.38 | 17.9× | |

| 🇷🇺 Rus | 0.54 | 3.41 | 10.6× | 🇺🇦 Ukr | 0.56 | 4.03 | 10.6× | |

| 🇬🇷 Gre | 0.31 | 7.04 | 22.5× | 🇦🇲 Arm | 0.34 | 4.18 | 17.5× | |

| 🇹🇷 Tur | 0.81 | 6.78 | 11.7× | 🇬🇪 Geo ¹ | 0.65 | 10.56 | 24.2× | |

| 🇮🇱 Heb ⁰ | 0.65 | 9.52 | 13.7× | 🇸🇦 Ara ⁰ | 1.17 | 9.85 | 9.8× | |

| 🇮🇷 Per ⁰ | 0.41 | 11.83 | 43.1× | 🇨🇳 Chi ⁰ | 0.43 | 20.07 | 103.0× | |

| 🇧🇩 Ben ⁰ | 0.72 | 11.03 | 25.9× | 🇮🇳 Tam ⁰ | 1.09 | 11.70 | 21.0× | |

| 🇯🇵 Jap ⁰ | 0.52 | 11.56 | 26.7× | 🇰🇷 Kor ⁰ | 2.98 | 11.58 | 3.5× |

⁰ Those speeds for caseless benchmarks are mostly dependent on the data location. Not only are those scripts caseless, but furthermore - many don’t use whitespace to mark word boundaries, so the benchmark is often running on much longer input queries than a single word. Expect over 10 GB/s in most cases and over 30 GB/s for cached data. ¹ Georgian is effectively caseless in most modern text, but Unicode case folding still touches it via historical mappings, so it currently can’t be accelerated with the ASCII-agnostic path. In the future it will require a custom script.

Our target is to reach 5 GB/s - the typical upper bound of a single NVMe SSD read speed or the approximate RAM throughput per core of modern many-core CPUs. That target has been met for almost all languages, except Russian, Ukrainian, and Armenian. Still, those already achieve 10–20× speedups over the serial baseline and will be improved further in future releases.

StringZilla Against ICU and MemChr

The Rust icu crate provides case-folding functionality, but not case-insensitive substring search.

Note that this crate is actually ICU4X—a modern reimplementation of ICU in Rust by developers from Mozilla, Google, and the original ICU4C project—rather than bindings to ICU4C.

So we do what most programmers do as a shortcut for such functionality - we case-fold the haystack and the needle, and then search one inside the other.

To fold we use icu::CaseMapper::fold_string and to search - the traditional memchr::memmem::Finder.

Those will yield different match offsets, but the overall number of matches will be the same - good enough for a benchmark.

| Dataset Language | ICU, GB/s | SZ, GB/s | SZ Gains | Dataset Language | ICU, GB/s | SZ, GB/s | SZ Gains | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🇬🇧 Eng | 0.08 | 12.79 | 152.0× | 🇮🇹 Ita | 0.08 | 12.99 | 153.0× | |

| 🇳🇱 Dut | 0.09 | 12.61 | 142.0× | 🇩🇪 Ger | 0.08 | 10.67 | 126.0× | |

| 🇫🇷 Fra | 0.09 | 10.77 | 123.0× | 🇪🇸 Spa | 0.09 | 11.62 | 132.0× | |

| 🇵🇹 Por | 0.09 | 10.72 | 125.0× | 🇵🇱 Pol | 0.09 | 10.50 | 122.0× | |

| 🇨🇿 Cze | 0.09 | 7.41 | 82.0× | 🇻🇳 Vie | 0.11 | 4.25 | 40.0× | |

| 🇷🇺 Rus | 0.14 | 7.12 | 50.0× | 🇺🇦 Ukr | 0.14 | 8.88 | 63.0× | |

| 🇬🇷 Gre | 0.13 | 2.57 | 20.0× | 🇦🇲 Arm | 0.19 | 0.98 | 5.3× | |

| 🇹🇷 Tur | 0.09 | 8.18 | 96.0× | 🇬🇪 Geo ¹ | 0.19 | 1.03 | 5.5× | |

| 🇮🇱 Heb ⁰ | 0.19 | 34.54 | 181.0× | 🇸🇦 Ara ⁰ | 0.20 | 38.55 | 196.0× | |

| 🇮🇷 Per ⁰ | 0.19 | 26.22 | 139.0× | 🇨🇳 Chi ⁰ | 0.24 | 25.65 | 106.0× | |

| 🇧🇩 Ben ⁰ | 0.30 | 28.20 | 95.0× | 🇮🇳 Tam ⁰ | 0.27 | 29.53 | 110.0× | |

| 🇯🇵 Jap ⁰ | 0.22 | 21.71 | 101.0× | 🇰🇷 Kor ⁰ | 0.23 | 35.10 | 150.0× |

The StringZilla numbers in this table are obtained from separate runs of the StringWars Rust suite, different from the StringZilla’s own C++ benchmarks that compare internal backends against each other - so the numbers may slightly differ from the previous table.

Despite the fact that raw memmem throughput can exceed 10 GB/s on already-folded text, the fold & scan pipeline is typically dominated by case folding, and sits around 100-300 MB/s.

A typical throughput of StringZilla’s fold & scan pipeline is between 5 and 15 GB/s, suggesting a 50× improvement.

StringZilla Against PCRE2

PCRE2 is the workhorse of the digital age. It’s by far the most popular RegEx engine ever written. It’s not even remotely as fast as Geoff Langdale’s HyperScan or Andrew Gallant’s Rust RegEx engine, but it’s one of the few that support full Unicode case-insensitive matching. RegEx is clearly a lot harder than substring search, but in the absence of better reference points, I’m also sharing the numbers one can get with PCRE2, enabling its JIT engine to precompile the automata for every needle, and excluding that time from benchmarks.

| Dataset Language | PCRE2, GB/s | SZ, GB/s | SZ Gains | Dataset Language | PCRE2, GB/s | SZ, GB/s | SZ Gains | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🇬🇧 Eng | 1.42 | 12.79 | 9.0× | 🇮🇹 Ita | 0.26 | 12.99 | 51.0× | |

| 🇳🇱 Dut | 0.37 | 12.61 | 34.0× | 🇩🇪 Ger | 1.24 | 10.67 | 8.6× | |

| 🇫🇷 Fra | 0.13 | 10.77 | 80.0× | 🇪🇸 Spa | 0.98 | 11.62 | 12.0× | |

| 🇵🇹 Por | 0.64 | 10.72 | 17.0× | 🇵🇱 Pol | 0.22 | 10.50 | 48.0× | |

| 🇨🇿 Cze | 0.28 | 7.41 | 27.0× | 🇻🇳 Vie | 0.03 | 4.25 | 134.0× | |

| 🇷🇺 Rus | 0.25 | 7.12 | 28.0× | 🇺🇦 Ukr | 0.21 | 8.88 | 42.0× | |

| 🇬🇷 Gre | 0.37 | 2.57 | 6.9× | 🇦🇲 Arm | 0.42 | 0.98 | 2.3× | |

| 🇹🇷 Tur | 0.44 | 8.18 | 19.0× | 🇬🇪 Geo ¹ | 0.33 | 1.03 | 3.1× | |

| 🇮🇱 Heb ⁰ | 0.25 | 34.54 | 137.0× | 🇸🇦 Ara ⁰ | 0.30 | 38.55 | 128.0× | |

| 🇮🇷 Per ⁰ | 0.19 | 26.22 | 141.0× | 🇨🇳 Chi ⁰ | 0.94 | 25.65 | 27.0× | |

| 🇧🇩 Ben ⁰ | 0.73 | 28.20 | 39.0× | 🇮🇳 Tam ⁰ | 0.26 | 29.53 | 114.0× | |

| 🇯🇵 Jap ⁰ | 0.89 | 21.71 | 24.0× | 🇰🇷 Kor ⁰ | 0.65 | 35.10 | 54.0× |

The StringZilla numbers in this table are exactly the same as in the previous table, only the baseline has changed from ICU to PCRE2.

It’s clearly not an apples-to-apples comparison, but if you are writing scripts with lots of case-insensitive matching, be informed that a better option exists.

Funny enough, in 2019, 4 years into building Unum, before moving to Armenia, I’ve spent several days working on a RegEx engine leveraging similar optimizations to the ones described here, but still lost to HyperScan at the time. Six years have passed and just like every other geek passionate about software - there is always one more project to finalize before returning to that one!

StringZilla Against ICU Built-in Search

I’ve just told you that ICU doesn’t provide case-insensitive substring search two paragraphs ago. 100× speedups don’t exist. This article is clearly a scam 😂

ICU has bindings for various languages, though the implementations differ.

Python’s PyICU wraps the original ICU4C.

Unlike the Rust crate, the Python binding does expose substring search functionality:

| |

Luckily, StringWars benchmarks have Python counterparts, and StringZilla also has pure CPython METH_FASTCALL bindings (some of the thinest in the industry, of course).

Moreover, Python has a separate RegEx library written by Matthew Barnett in C.

It implements full Unicode casefolding, correctly handles the German example in the beginning of this article, and is quite easy to use:

This might be an interesting comparison point, assuming its the same workload for the same datasets, but a different language.

| Dataset Language | ICU, GB/s | RegEx, GB/s | SZ, GB/s | Dataset Language | ICU, GB/s | RegEx, GB/s | SZ, GB/s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🇬🇧 Eng | 0.06 | 0.77 | 5.61 | 🇮🇹 Ita | 0.06 | 0.97 | 8.87 | |

| 🇳🇱 Dut | 0.06 | 0.86 | 7.99 | 🇩🇪 Ger | 0.06 | 0.90 | 6.08 | |

| 🇫🇷 Fra | 0.06 | 1.10 | 6.83 | 🇪🇸 Spa | 0.06 | 1.02 | 6.33 | |

| 🇵🇹 Por | 0.06 | 1.10 | 8.12 | 🇵🇱 Pol | 0.06 | 1.29 | 8.02 | |

| 🇨🇿 Cze | 0.06 | 1.38 | 6.36 | 🇻🇳 Vie | 0.05 | 1.07 | 1.12 | |

| 🇷🇺 Rus | 0.10 | 2.30 | 5.70 | 🇺🇦 Ukr | 0.10 | 2.26 | 5.35 | |

| 🇬🇷 Gre | 0.09 | 1.38 | 2.48 | 🇦🇲 Arm | 0.11 | 2.07 | 0.86 | |

| 🇹🇷 Tur | 0.06 | 1.49 | 5.25 | 🇬🇪 Geo | 0.16 | 3.20 | 0.62 | |

| 🇮🇱 Heb | 0.11 | 2.92 | 15.72 | 🇸🇦 Ara | 0.08 | 3.01 | 14.78 | |

| 🇮🇷 Per | 0.09 | 2.36 | 10.70 | 🇨🇳 Chi | 0.09 | 5.40 | 13.94 | |

| 🇧🇩 Ben | 0.14 | 4.51 | 21.19 | 🇮🇳 Tam | 0.16 | 5.81 | 23.11 | |

| 🇯🇵 Jap | 0.10 | 4.88 | 13.17 | 🇰🇷 Kor | 0.06 | 4.59 | 20.05 |

I was genuinely quite surprised that the regex module outperformed stringzilla on Armenian, so there must be a lot more things I can optimize in future releases.

In the meantime, feel free to reproduce the benchmarks on your hardware, but keep in mind that the numbers won’t be as impressive if you don’t have AVX-512.

More ISA backends will come in the future.

Reproducing Benchmarks

The original Serial vs AVX-512 benchmarks can be found right inside the StringZilla repository. To run it locally:

| |

For the Rust StringWars suite the similar environment variables can be used:

Similarly, for the Python benchmarks:

To run on the same files, fetch the datasets listed in StringWars, and pull them with curl like this:

| |

Kernel Optimizations

Every script family has its own folding kernel and “alarm”. The fold rewrites bytes in place so probes can reuse the same verifier, while the alarm spots ligatures or shrinking expansions that require a slow-path correction. The “naive” approach is to check equality against each byte value, then prefix-AND masks of consecutive 1-, 2-, or 3-byte sequences, and finally OR all danger masks together.

In the Unicode 17 folding tables we target, multi-codepoint fold expansions never produce 4-byte UTF-8 sequences, so the expansion slow-path can safely ignore them.

That, however, introduces a remarkable amount of port pressure on x86 CPUs.

The VPCMPB K, ZMM, ZMM instruction takes:

- 3 cycles on port 5 on Ice Lake.

- 5 cycles on ports 0 or 1 on AMD Zen 4.

Shifting the produced masks between K registers and ALUs and expanding them back to ZMMs for further processing is similarly expensive.

So next to every “naive” baseline kernel for AVX-512 - I wrote “efficient” versions using harder-to-trace logic, but comparing every streamed-through buffer against the “naive” baseline in debug builds to ensure correctness.

Equality Comparisons Port Pressure

The Western/Central alarms originally hammered port 5 with 12+ equality checks every 64 bytes.

By compressing entire ranges into a single subtraction + comparison and deriving the actual member with VPTESTNMB, we freed the port for real work.

Central Europe performs the same trick for the C3–C5 block: one range check plus two ternary tests produce the ‘K’/‘ß’/‘İ’/‘ſ’ masks without congesting the execution unit.

Ternary Logic and Blends

The ASCII fast path leans on ternary logic.

For ≤3-byte windows we broadcast the first/middle/last byte, XOR the haystack at three offsets, merge via VPTERNLOG (imm8 0xFE), and let VPTESTNMB turn zero lanes into positions.

No extra window replay is needed because all bytes are covered.

For ≥4-byte windows we add a fourth probe plus a cached 16-byte window.

Once the probes line up we replay the window via _mm_maskz_loadu_epi8 and only then call the shared verifier.

The Greek folding kernel benefits from ternary logic even more: it builds five independent offset vectors (e.g., +0x20, -0x20, +0x26, +0x25, -1) and collapses them with two chained VPTERNLOGs before a single _mm512_add_epi8.

That removes the eight-step mask-move chain we previously had and keeps port 5 from saturating.

Byte-Table Shuffles

Greek and Cyrillic folds use VPSHUFB lookups instead of branchy ranges.

We mask off the high nibble of each continuation byte, shuffle a 16-entry table, and add the resulting offset back to the register—three disjoint subranges handled in one go.

For Greek we encode per-range offsets in a single LUT so that one shuffle handles the entire CE lead byte:

+0x26for 'Ά'U+03860x CE 86and friends+0x25for 'Έ'U+03880x CE 88, 'Ή'U+03890x CE 89, 'Ί'U+038A0x CE 8A+0x20for 'Α'U+03910x CE 91– 'Ο'U+039F0x CE 9F-0x20for 'Π'U+03A00x CE A0– 'Ω'U+03A90x CE A9and dialytika cases

Cyrillic is even tidier: every uppercase lives in D0 80–D0 AF, and every lowercase twin sits either +0x10, +0x20, or -0x20 away in the same byte lane.

Mapping the high nibble of the 2nd UTF-8 byte (8, 9, A) into those offsets lets a single VPSHUFB drive the entire block, while a post-shuffle mask flips D0→D1 whenever the nibble was 8 or A.

Using StringZilla

At this point you must be itching to try it out. StringZilla is available under the Apache 2.0 license on GitHub: github.com/ashvardanian/StringZilla. Several language bindings already have the Unicode functionality exposed. One important detail: offsets and lengths in the Unicode APIs are in bytes, not codepoints.

C and C++ APIs

StringZilla is header-only.

No linking, no runtime deps, no nonsense.

Copy the headers, add a submodule, or use CMake FetchContent:

But if you are building Operating Systems, Browsers, or Database Engines - you can probably tolerate some extra legwork if it brings you multi-versioned kernels with dynamic dispatch at runtime. It means compiling StringZilla as a separate library with all ISA backends enabled, shipping it alongside your binaries, and expecting it to automatically detect if the CPU supports every weird SIMD instruction set you care about.

If you want to further reduce the latency of dynamic dispatch and use some other feature-detection mechanism, you can still manually address the different backends, grab the function pointers, and call them directly:

| |

Unicode case folding expands characters, so the output buffer must be at least 3× larger than the input.

The case-insensitive search API returns a pointer to the start of the first match (or NULL if not found).

It also outputs the length of the matched substring in bytes, which can differ from the needle length due to expansions.

| |

In C++ the same functionality is exposed on string views and via a pre-compiled needle type:

CPython Bindings

StringZilla is in the top 1% of Python’s most downloaded packages on PyPI. Installation should be trivial:

| |

It will pull one of the 96 platform-specific wheels compiled per release, at the time of writing.

I love to flex, that for comparison, NumPy ships 74 wheels per release. And unlike NumPy, StringZilla doesn’t redirect calls to your BLAS (or LibC in this case) - it ships hand-rolled kernels for every popular ISA family. Oh… and there is also a separate package for parallel extensions on GPUs and high core-count CPUs, which makes this comparison even more unfair. So in case you are doing Web-scale LLM dataset preprocessing Common Crawl at some Frontier AI lab or aligned/sketching Petabytes of protein and DNA data - to snatch the next Biology Nobel Prize before AlphaFold 4 comes out, install one of these too:

More on this topic in the “Processing Strings 109x Faster than Nvidia on H100” post 🤗

Once installed, case-insensitive search is a one-liner:

For repeated searches, use the iterator - it can reuse internal needle metadata:

Rust Bindings

Same story in Rust:

| |

You get both a one-off function and a pre-compiled needle type:

| |

Swift Bindings

Add the package in SwiftPM:

Then search:

Node.js Bindings

JavaScript bindings are available via NPM:

| |

That said, due to the extreme fragmentation of the JavaScript ecosystem - I’m never quite sure about how smooth the installation will be on your environment.

There are also limitations to accessing the internal contents of strings in JavaScript, so the API expects Buffers instead of strings.

That’s true for pretty much all of StringZilla functionality in Node.js.

| |

GoLang Bindings

GoLang installation might be the trickiest, as it uses a different Assembly syntax and calling convention.

Yes, you still need to go get the package, but before that you need to pull the precompiled shared libraries from GitHub Releases and place them in your dynamic linker path:

| |

You can grab the binaries from GitHub Releases.

On Linux, that’s typically LD_LIBRARY_PATH. On macOS, that’s DYLD_LIBRARY_PATH.

Sadly, that’s a common limitation of Go. Moreover, switching from Go’s lightweight goroutines to OS threads for calling into C is also quite expensive, so you won’t win much unless you are calling into a longer operation. It meant limited applicability of StringZilla in Go for operations like hashing and exact substring search, but case-insensitive search over Unicode is a much better fit, so the bindings are available:

Future Plans

There are clearly some blind spots in the library. Georgian script deserves its own SIMD kernels, Korean and other language performance can also clearly be improved. Even more importantly, porting this to Arm won’t be trivial. I don’t expect this workload to benefit much from SVE2, so NEON will be the main target. It’s limited to 128-bit vectors, so to stick to the same 64-byte wide blocks with up-to 16-byte safe slices, we’ll need to process 4 vectors in parallel, also covering inter-register boundaries with intra-register shuffles…

I won’t be doing that tomorrow. There is one more massive open-source release I want to finish this year and you’ll never guess what it is about, but here’s a hint 😉

This is the ugliest, but potentially the most important piece of open-source software I've written this year.

— Ash Vardanian (@ashvardanian) December 15, 2025

In short: I grouped all Unicode 17 case-folding rules and wrote ~3K lines of AVX-512 kernels around them to enable fully compliant case-insensitive substring search… pic.twitter.com/uKz0QyU6FO